TL;DR: In 2025, two trends are colliding: AI enables small teams to build at unprecedented speed, while venture capital is becoming less necessary for many startups. At the intersection of these trends, a new type of company is emerging—exemplified by Every, a hybrid organization that is neither a traditional media company nor a conventional startup. — Daniel

Was this email forwarded to you?

Join curious founders, creators, and investors by subscribing below:

Memo

Either write things worth reading or do things worth writing.

—Benjamin Franklin

Why not both?

Every was founded by Dan Shipper and Nathan Baschez back in 2020.

It started as The Everything Bundle, a collection of newsletters on Substack.

Key milestones over the past five years:

Published 1,500 essays

Reached nearly 4,000 paid subscribers.

Hit $60,000 in MRR and over $3 million in total revenue.

Incubated three software products.

Launched courses on writing, programming, and psychology.

Built a full-time team of seven.

Every raised a pre-seed round from Eric Stromberg but they’re primarily self-funded.

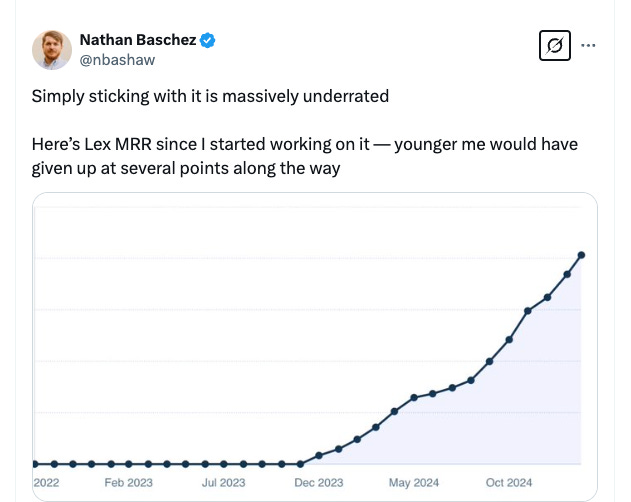

In 2023, Nathan spun out Lex (Cursor for Writing) as a separate company, which has experienced significant growth recently.

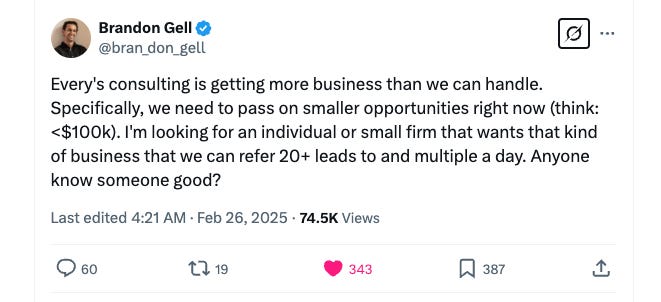

Last year, Every ventured into consulting, which has been so successful they’re overwhelmed with requests and asking for help.

One key thing that shouldn’t be overlooked is their taste.

It’s a clear strength.

Their design aesthetic and UX sensibilities are impressive.

How should we define Every?

Media Company?

Bootstrapped Startup?

Writer Collective?

Dan Shipper recently spoke with venture capitalist Nabeel Hyatt about the challenge of fully defining Every.

I feel like I've been grasping for words for how to describe what Every is for a while. I think that's a really interesting place to be because we're doing something that's working and there isn't yet a word for it. The closest thing I've come up with is multi-modal media company. — Dan Shipper

The absence of a clear definition for Every suggests they’re probably predicting the future by inventing it. When organizations operate at the frontier of innovation, they often defy easy categorization. This ambiguity can actually be a sign of genuine novelty rather than confusion or lack of focus.

Think, Build, Ship

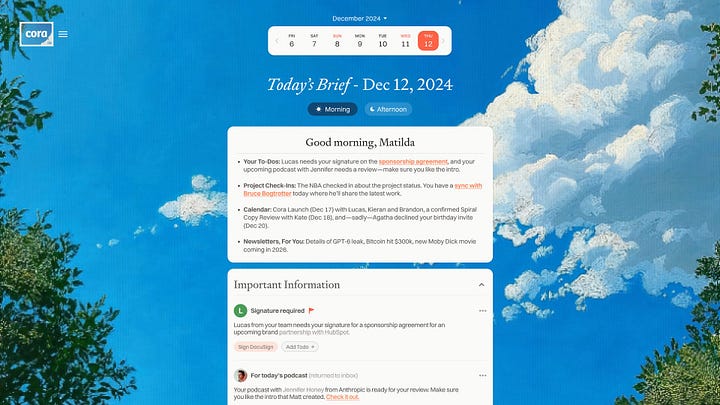

Every Studio, their in-house incubator, is fueled by generative AI. The Studio supports a group of Entrepreneurs-in-Residence (EIRs) to think, build, and ship products that solve problems close to home. For each idea, they’ll do an Alpha release internally and if it passes the sniff test, its released to the public.

Some thoughts from Dan:

Our EIRs are building products that they want to use themselves. They’re solving problems that they’ve encountered living in the future.

We’re entering an era of gritty startups where rapid experimentation and distribution to a dedicated audience is the most exciting way to build new businesses.

Can they scale?

In a world where you can build and launch a prototype in an afternoon, scale can be an afterthought. We’ve created a model with optionality at its core—letting an idea become its best expression, whether as an experiment, a cash-flow business, or the next Apple.

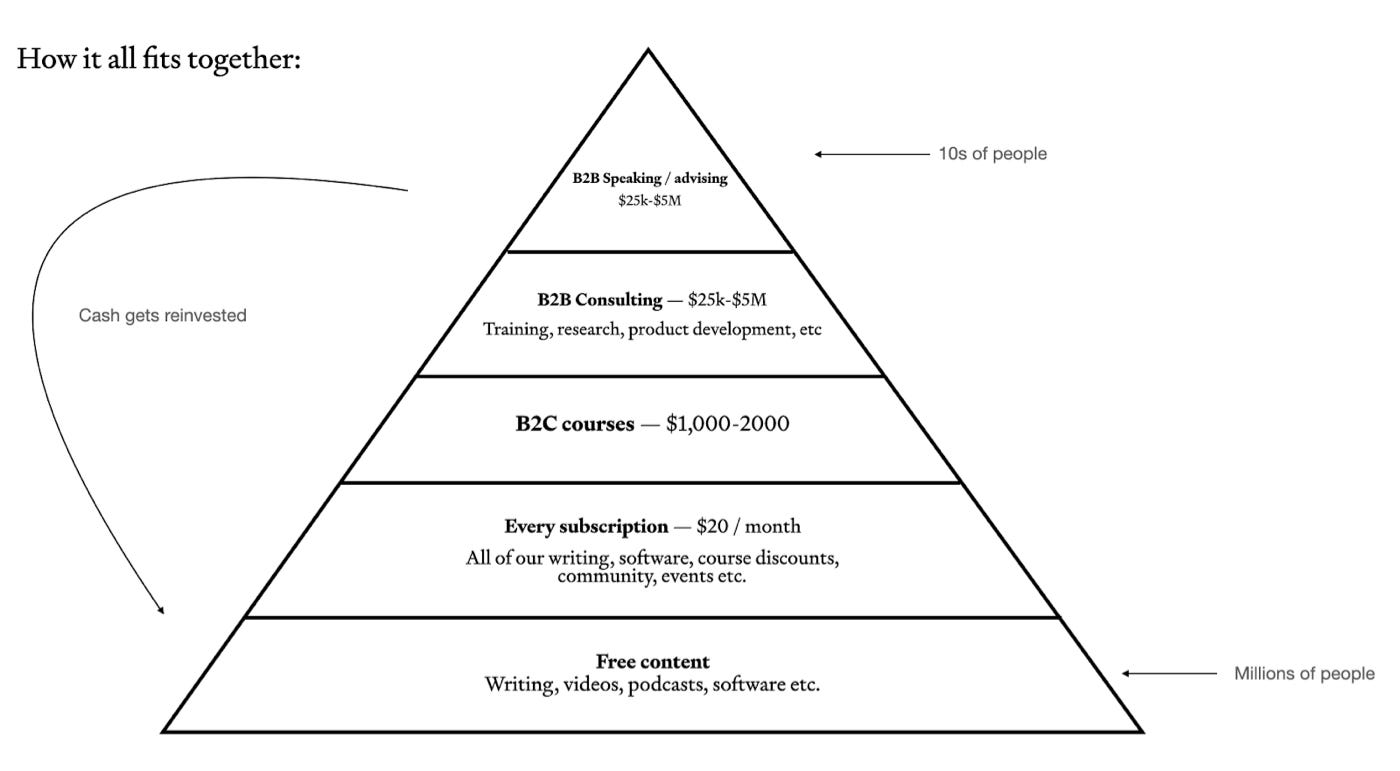

How much do all of their products cost?

Every-thing is included in a $20 monthly subscription.

I’m bullish on this model. My investment thesis is predicated on a future powered by creators, collectives, and guilds.

A virtuous cycle

Every operates on a self-sustaining loop.

Podcast interviews support their newsletter.

The newsletter is an owned distribution channel for launching products.

Products drive more newsletter subscribers, who then subscribe to their podcast and share their essays.

Many startups struggle with customer acquisition, but Every leverages its existing audience like kindling for a fire.

That’s how you get 10,000 signups in a month for an email app.

They’ve earned a ton of trust from years of publishing thought provoking essays.

That trust is paying handsome dividends now.

Building products inside of a beloved media company is an unfair advantage.

The absence of venture dollars

Every raised a small "speed round" of $150K, primarily from Gumroad founder Sahil Lavingia. Given their revenue and distribution, they didn't need much capital.

They could likely raise a large VC round today, but they seem more interested in maintaining optionality and control.

Every is a classic example of the tension between founders who want to grow software businesses without massive venture capital and investors who only fund companies willing to scale aggressively.

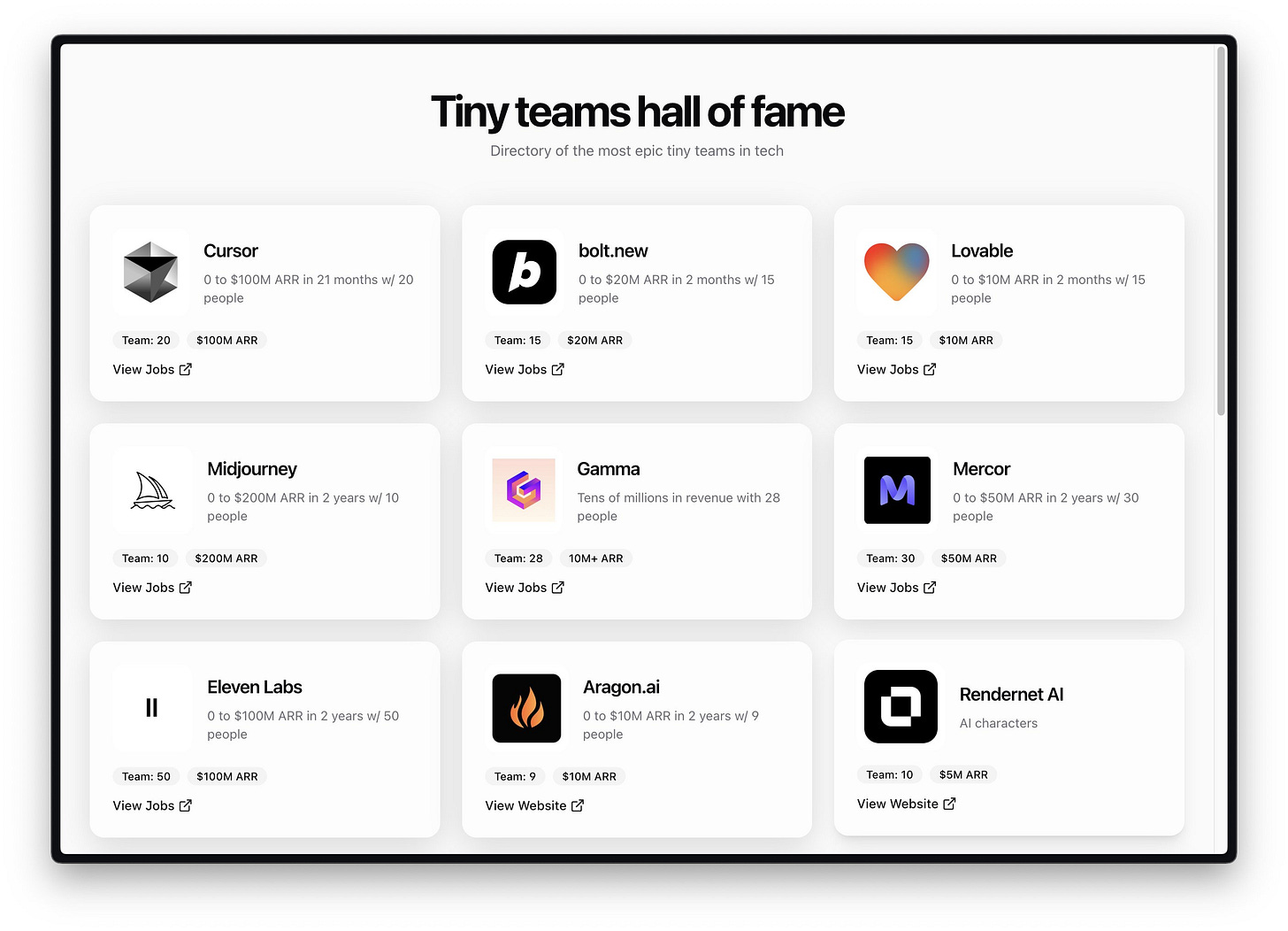

It’s no secret that AI has thrown lighter fluid on the bootstrapped startup model.

This raises an important question.

Why build a Series A fund if most startups no longer need VC money to scale?

Some firms are already adapting by offering more flexible terms, smaller check sizes, and revenue-based financing options.

Bootstrappers have always presented a challenge to traditional VC firms, but this moment feels more like an existential threat.

Pre-Seed and Seed Stage Startups are far more capital efficient now, and AI is allowing small teams to produce an astonishing amount of work in a fraction of the time it used to take just a couple years ago.

Cursor reached $100M ARR with just 20 employees.

The first version of Spiral was built in a couple of days.

Quick aside, this will be a recurring theme here: the increasing viability of startups that opt out of the traditional funding ladder and its impact on venture capital.

How Every could fail

Three structural challenges could derail Every's model:

1. The Talent Paradox

Every's model creates a unique talent retention problem. By design, they attract entrepreneurial stars and help them build valuable products. But this success creates natural exit pressure:

EIRs who build successful products have strong incentives to spin them out completely or leverage their success to raise money for a new venture

The more valuable the product becomes, the stronger these incentives grow

Unlike traditional companies where success aligns everyone's interests, Every's success can actually accelerate team departures

This isn't just about compensation—it's about ownership and control. Even generous profit-sharing may not compete with the pull of full autonomy.

2. Shiny Objects

Every's reputation rests on maintaining high editorial standards while they fall down software rabbit holes. This creates competing pressures:

Editorial excellence requires deep focus and careful curation

Software development with AI feels like a slot machine that’s hard to step away from without discipline

Chasing too many shiny objects could be a distraction

3. Consumer Fatigue

While Every's media platform provides powerful distribution for new products, this advantage has hidden costs:

Each new product launch taxes their audience's attention

Failed products risk damaging the invaluable trust they've built

Users might grow weary of more micro-apps that solve only one problem

These fundamental tensions in their business model will require careful navigation. The real test isn't whether they can launch products quickly, it's whether they can preserve what makes Every special.

What are your thoughts?

How could Every fail, and are these points valid?

Let me know in the comments.

Fin

As AI tools continue to evolve, we'll likely see more companies following Every's hybrid model—leveraging content creation, community building, and product development in symbiotic ways.

The future of startups might not belong to unicorns chasing hyper-growth, but to thoughtful companies building valuable solutions while maintaining independence and creative control. A collective of writers, engineers, and designers that can manage a portfolio of software companies under one roof.

Every reminds me of an indie rock band. Their success isn't built on mass-market appeal or huge marketing budgets, but on authenticity and a distinctive voice that resonates deeply with their audience.

Indie bands often succeed by ignoring conventional wisdom and Every has certainly sidestepped traditional startup playbooks. They've built their following through consistent creative output rather than growth hacks or viral marketing.

Every's success isn't threatened by others copying them. Their competitive advantage lies in their distinctive voice and sensibility—something that can't be replicated with capital or technology alone.

Indie artists can thrive by cultivating a dedicated fanbase who'll buy each album, attend every show, and support their artistic evolution. Every has over 10,000 true fans who will back them not just because of their ideas, but because of their taste.

Writing is the most important skill in the agentic age. A collective of writers, paired with engineers and a brilliant designer, is a scary good group to build with.

— Daniel

I appreciate your feedback. If you enjoyed this piece, drop a like or comment below. You can also send a note to daniel@hunter.vc, would love to hear from you.

Really nice article, congrats!